Voyage of discovery in modern times

By Craig Johnson

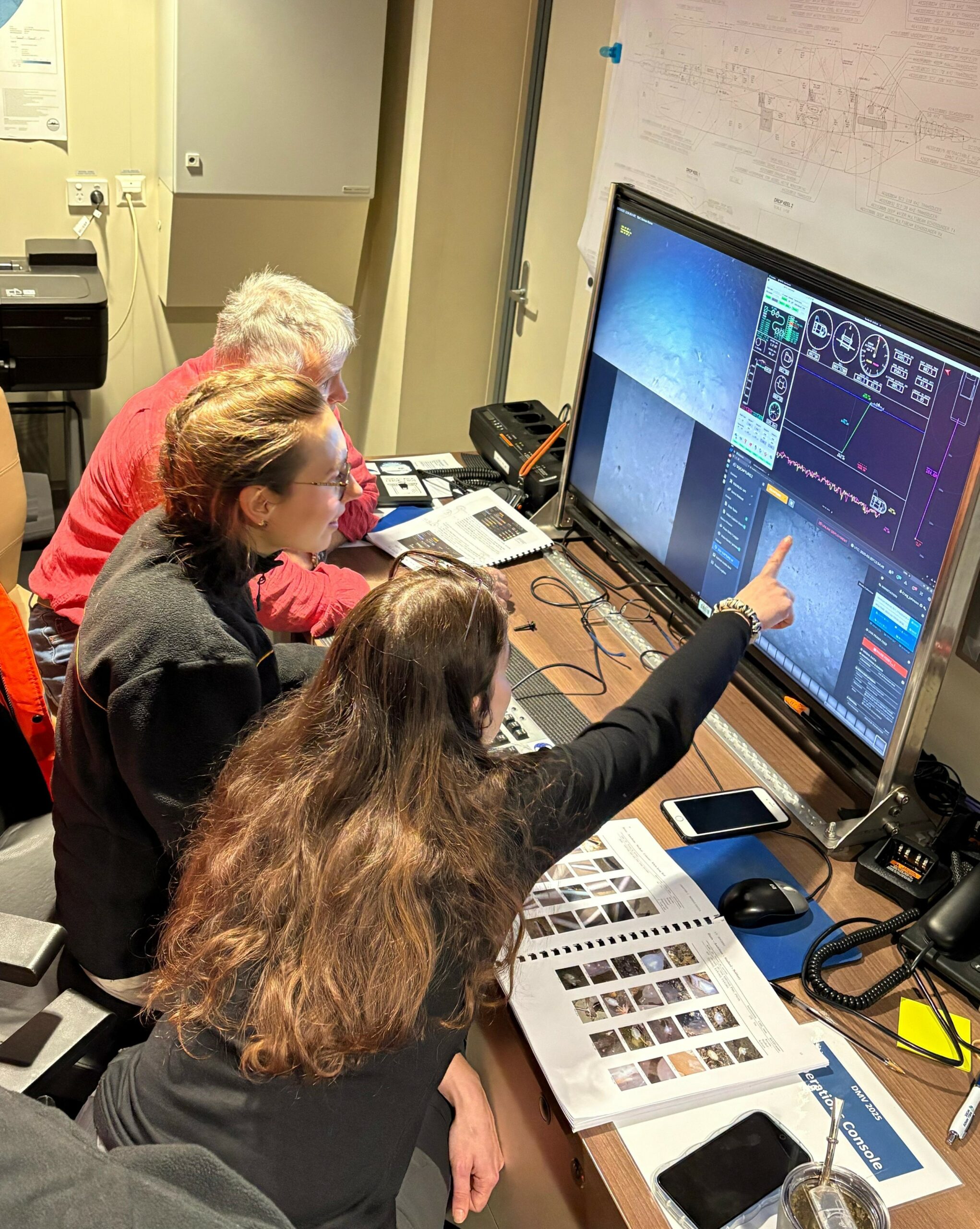

It’s -22 °C chill factor outside, the water is -1.75 °C, and for the last half-hour the ship has been manoeuvring to avoid ice bergs. I’m cosy in shirt sleeves, sitting in a comfortable chair in the science operations room, and with my two colleagues am gazing at a computer screen with much anticipation – excitement even. The team is about to dive a high-tech camera to ~1,600 m in a canyon off the edge of the continental shelf in eastern Antarctica so that we can look at and photograph the animals living on the sea floor. Nobody has ever done this in this area – it is real ‘voyage of discovery’ stuff.

I’m not the only one with a heightened sense of anticipation. It takes a big team of people, including deck crew, winch operators, IT specialists, electronics engineers, and the bridge crew to deploy this technology and fly the camera along the bottom. The whole room is drawn to the screens showing the camera feeds, and no one speaks. We watch as the camera drops through the water column, the lights picking out krill and other crustaceans, and the various ‘jelly animals’ look spectacular in the lights. Tonight there is also a lot of particulate matter in the water – marine snow, and the downward facing camera makes it look like flying though an asteroid belt.

The camera reaches the sea floor, and the ship begins to tow it across the bottom. The silence in the room gives way to sounds of delight as all manner of animals come into view. Bloated sea pigs and other species of sea cucumber, brittle stars, and sea stars feed on the organic material in the sediment, while spectacular feather stars (crinoids), sponges, fan worms, hydroids and sea whips (octocorals) filter their food from the water. There are large anemones, delicate bright red shrimps, various worms, and a variety of fish species captured in the frames. Whoa! There’s a fish with the tail of another fish protruding from its mouth.

This is the stuff that marine biologists dream of – watching sea floor communities in real time in one of the most remote habitats and inaccessible locations on earth. The video is being piped to screens in the ship’s mess and to the big screen in the theatre where some creative soul has provided an appropriate sound track. The theatre is some way down the corridor from the science operations room, but we can hear the cries of delight from the eager audience as yet another spectacular organism is picked up by the cameras. Once the cameras are back on deck, some of the theatre audience confess to me that they were in tears on occasions, overcome by what they were seeing.

Over the voyage, our camera tows are intended to sample as many different habitats as possible. Different depths, slopes, distances from the Denman Glacier, and different sea floor geologies. Once back on shore the images will be processed in meticulous detail, and the data used to inform models designed to predict the distribution of species, community types, and vulnerable marine ecosystems on the continental shelf around Antarctica. The maps we produce are vital to informed management of this very special place.

—

*Adjunct Professor Craig Johnson (IMAS) is a Senior Scientist and project lead for the benthic imagery team for ACEAS on the Denman Marine Voyage.