The magic of magnetotellurics: Imaging how deep Denman Glacier is and what lies far beneath

For the second summer running, ACEAS geophysicist Dr Maria Costanza (Coti) Manassero is camped in the remote Bunger Hills in East Antarctica, about 450 kilometres from Australia’s Casey Research Station.

It’s the last leg of the three-year Denman Terrestrial field Campaign, the sister project and precursor to the upcoming Denman Marine Voyage on icebreaker RSV Nuyina.

One campaign examines the enormous Denman Glacier from the land, the other from the sea.

Both are collaborative research missions between ACEAS, the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership (AAPP), Securing Antarctica’s Environmental Future (SAEF) and the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD).

“It’s a great feeling to be back. I love the place,” Dr Manassero says.

“Antarctica – I think it’s a place that everyone falls in love with.”

As a Postdoctoral Research Associate with ACEAS, Coti specialises in Magnetotellurics– a geophysical technique that uses the Earth’s natural electric and magnetic fields to image the subsurface, particularly the electrical conductivity distribution beneath the surface. This information helps to understand how deep glaciers are and their subglacial hydrology, which is related with glacial melting rates.

“By getting the data and by analysing it we can have information of the structures beneath the surface.”

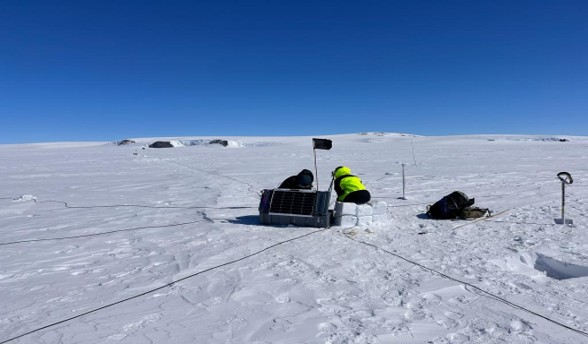

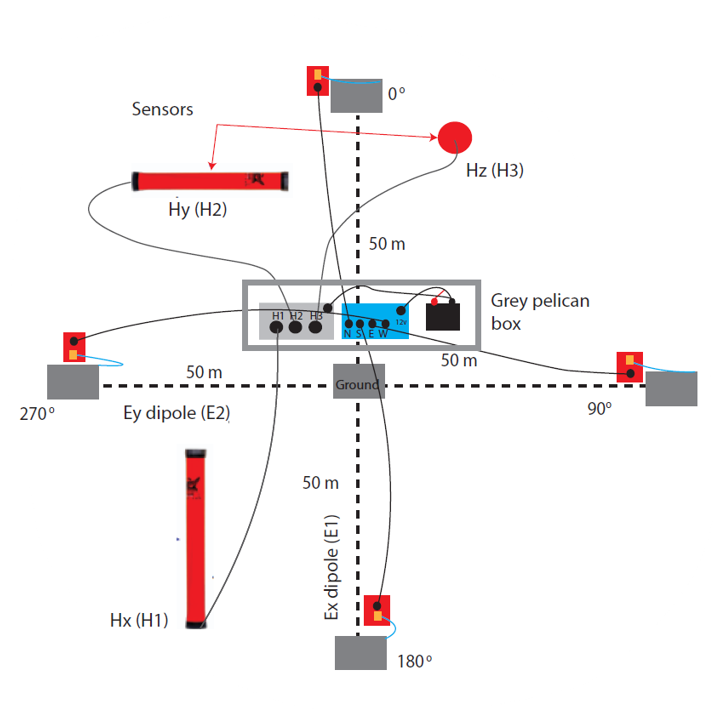

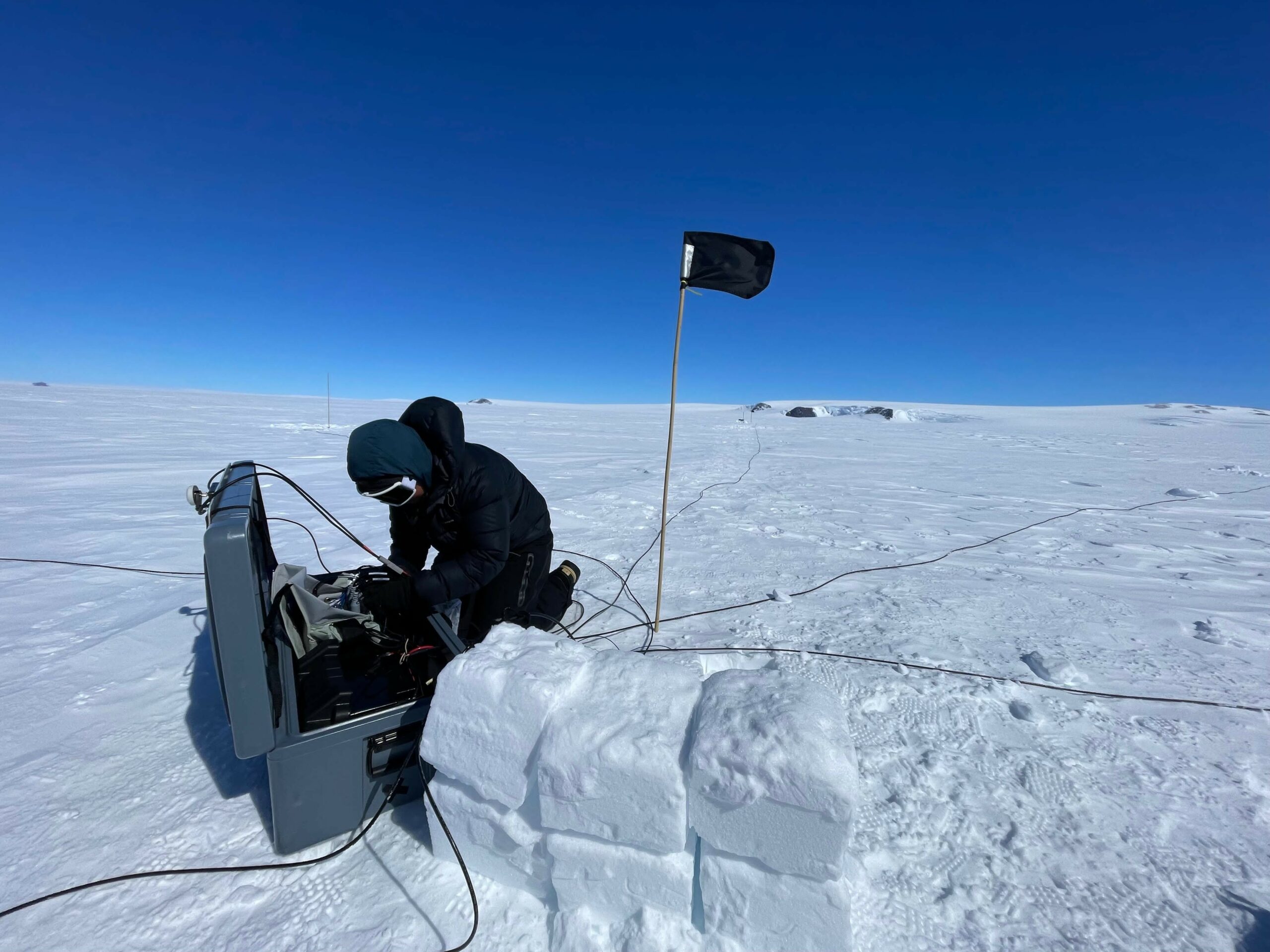

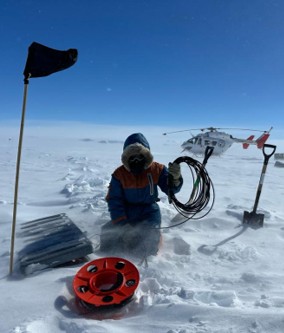

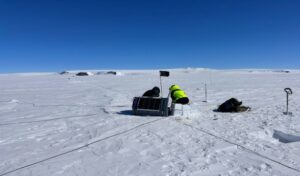

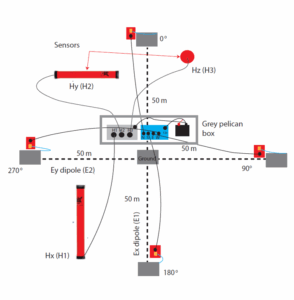

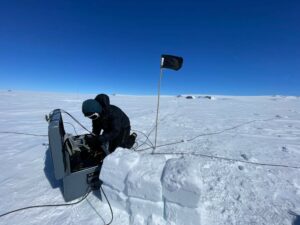

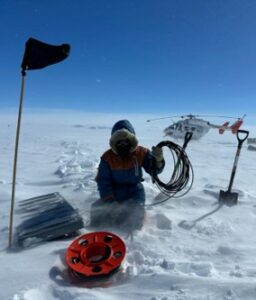

To do this, the research team lays down large, heavy tube-like coils called magnetometers on the surface of the ice, each about a metre and a half long that measure the Earth’s magnetic field. The electric fields are measured with titanium sheets called electrodes buried in the snow. Each station takes approximately 3-4 hs to deploy in good weather and 2-3 hs to retrieve.

“In order to deploy the magnetotelluric stations on the glacier and the Antarctic plateau we need a lot of help from the camp, the Field Training Officers (responsible for safety) and the pilots,” says Dr Manassero.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about this very specialised equipment being laid on and around the Denman Glacier is the sheer of the information we can obtain beneath the surface.

“The great thing about magnetotellurics is that, depending for how long you leave the instrument recording the natural electric and magnetic fields, the deeper you see into the earth,” Dr Manassero says.

“So if you leave the instrumentation recording for let’s say, two days, you will have information or a good image down to 20km beneath the surface. But if you leave it for let’s say 15 days or a month, you can get up to 400km, all the way down into the mantle.”

—

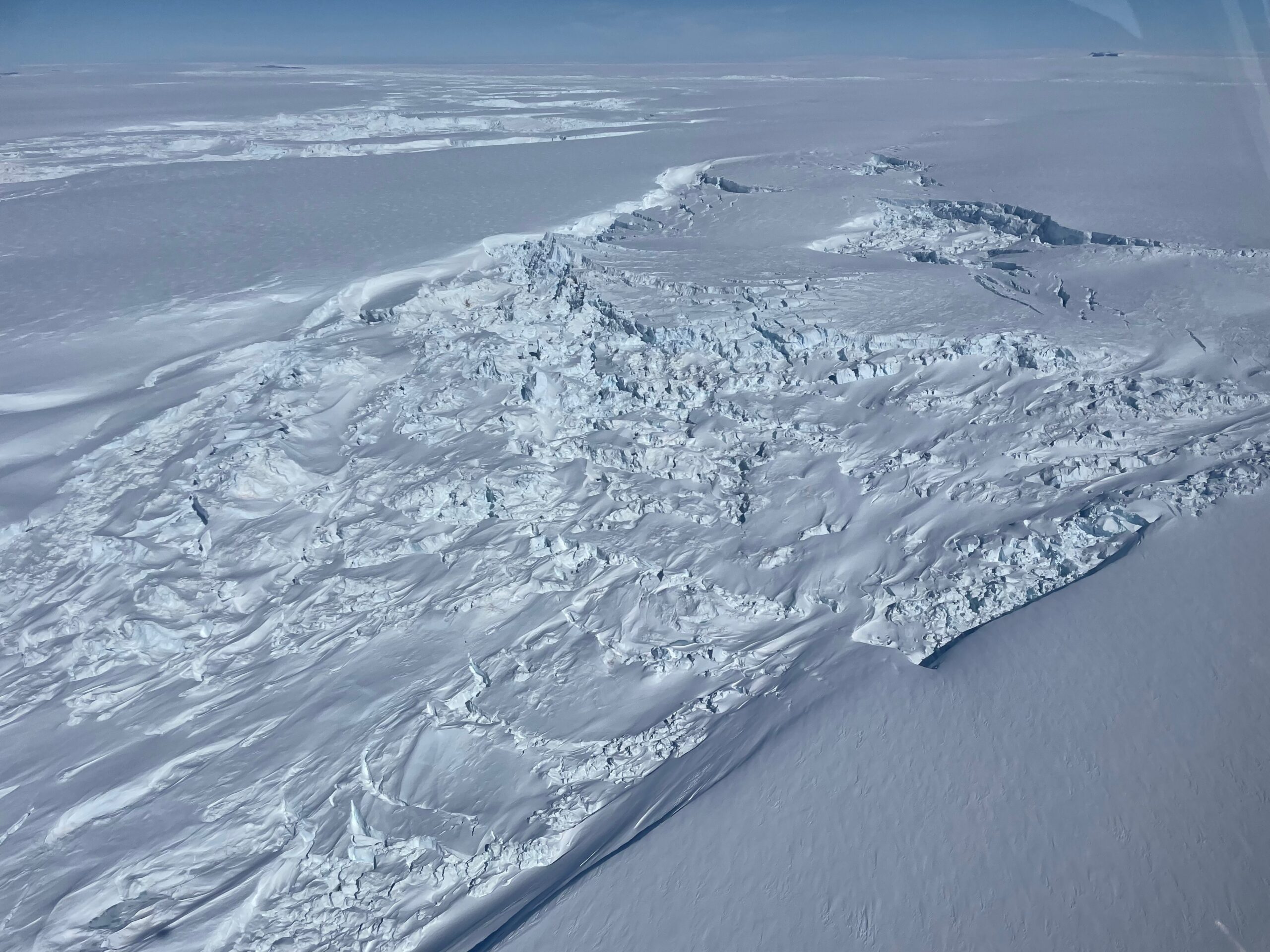

The Denman Glacier has been modelled as the deepest trough on earth, about 3.5 – 4km deep. So large is the Denman, if it were to completely melt it could raise sea levels globally by 1.5 metres. However, Denman Glacier has never been directly imaged before. This is the first time geophysical data has been obtained on the surface of the glacier, with the aim of determining how deep Denman Glacier actually is to improve ice sheet models and map the subglacial hydrology to understand melting rates.

“With magnetotellurics, we can see sub-surface hydrology and the contrast between ice and rock, to map ice thickness. We can also constrain the temperature and viscosity of the mantle, which is very important to improve GIA (Glacial Isostatic Adjustment) models,” says Dr Manassero.

The Earth’s mantle is described as the mostly solid bulk (estimated to be about 67% of the planet) of Earth’s interior. Once masses of ice are lost at the surface, the solid Earth rebounds at a rate determined by the mantle viscosity. Having information about mantle viscosity improves our understanding of ice loss in Antarctica.

For Dr Manassero, this summer’s trip is multidisciplinary.

She’ll also be helping colleagues on other Denman research projects, including the deployment of a long-term mooring into an epi-shelf lake linked to the ocean which will be sending crucial information to understand glacial melting; gravity and GNSS measurements to study the effect of ocean tides on epishelf lakes, and the retrieval of cameras and other equipment from last field season.

“Coming back for a second time now, it’s a really nice feeling to be able to help others and pass on the experience,” she says.

“l feel super connected with the Bunger Hills and with Antarctica. When you go there and you actually see how amazing, how beautiful it is and how things are changing so quickly, it hits you really hard.”

“You feel very invested in going there and doing the best you can to understand, to spread the word. I think as a scientist we have the responsibility of letting people know what’s happening, for Antarctica.”

—

*the Denman Terrestrial Campaign is a scientific collaboration between the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS), the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership (AAPP), Securing Antarctica’s Environmental Future (SAEF) and the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD). It is part of the Australian Antarctic Program (AAP)