Listening to the deep: how sound maps the seabed

By Laura De Santis, Senior Scientist (National Institute of Oceanography and Applied Geophysics OGS, Trieste, Italy) and Joline Lalime, Sea2SchoolAU

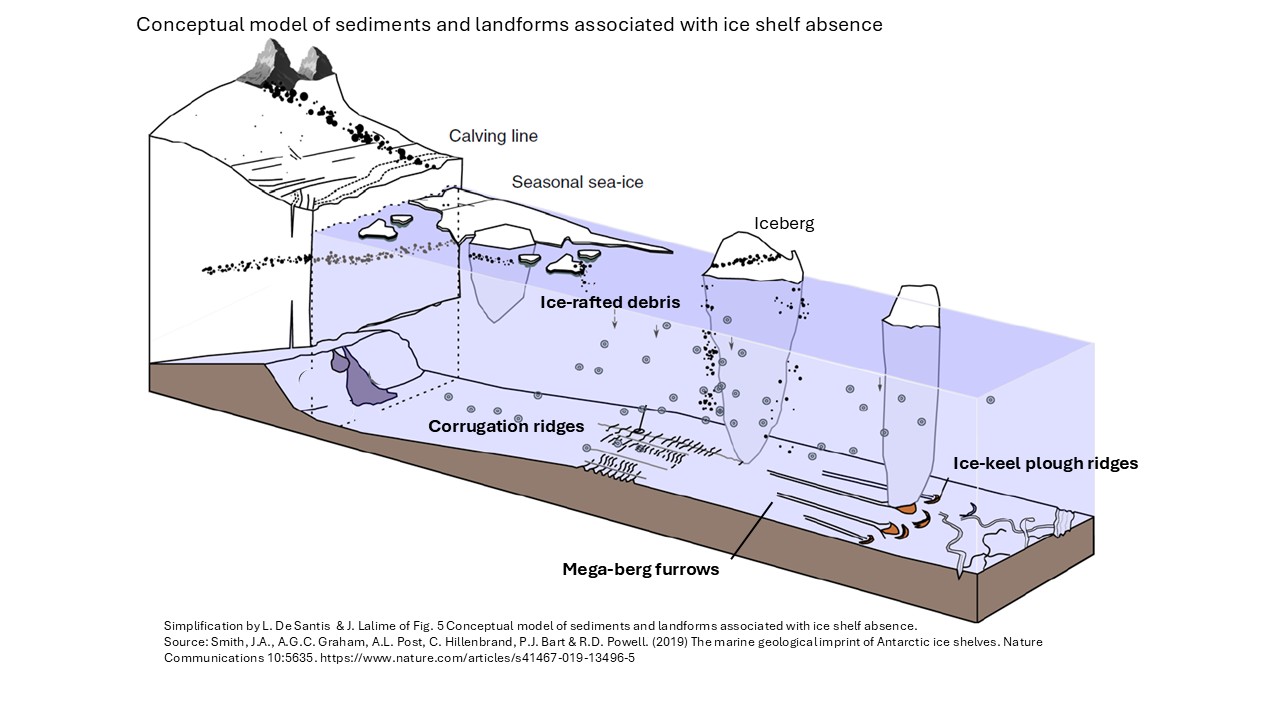

The seafloor in the region surrounding the Antarctic continent is not flat and uninteresting; rather, it is characterised by distinctive bedforms – wave-like features made of movable sediment – that reveal the processes that created them. These help us reconstruct the history of the ice sheet and ocean currents. For example, we can identify and map iceberg keel marks (grooves created by the bottom edge of a drifting iceberg), and sedimentary waves formed by bottom currents. We can also distinguish ‘morainal ridges’, which are an accumulation of rock, sand and clay that are the result of being pushed or deposited by glaciers. These ridges are typical bedforms on the seafloor and are used to recognise and map how ice streams (large rivers of ice), pushed out towards the ocean during past ice ages, known as glacial periods. We are now in a warm (interglacial) period. Approximately 20,000 years ago, the ice stream limit retreated by several kilometres; therefore, we can find older, palaeo-morainal ridges on the seafloor.

How do they form?

Ice has accumulated in the interior of the Wilkes Subglacial Basin (WSB) and has been flowing towards the coast primarily via the Ninnis and Cook ice streams for thousands of years. When the Cook Glacier reaches the ocean it forms the Cook Ice Shelf, meaning the WSB is the inland source that feeds the shelf. Large ice streams scrape the bedrock during their journey from the interior of the WSB to the sea, carrying rocks and sediment at their base. This debris is pushed, broken up, and tapered during its journey at the base of the flowing ice. As the ice streams reaches the ocean and melts, the sediment trapped in the base of the glacier is forced towards the front and deposited on the seafloor in the morainal ridges. These morainal ridges can then be reshaped by ocean currents, colonised by marine fauna, and covered by layers of other sediments and dead organisms. Iceberg keels can occasionally pin and modify them. Sometimes it is not easy to recognise morainal ridges. In any case, to determine what they are and how old they are, we must collect sediment cores similar to those mentioned in COOKIES Blog 3.

How are seafloor bedforms located and mapped?

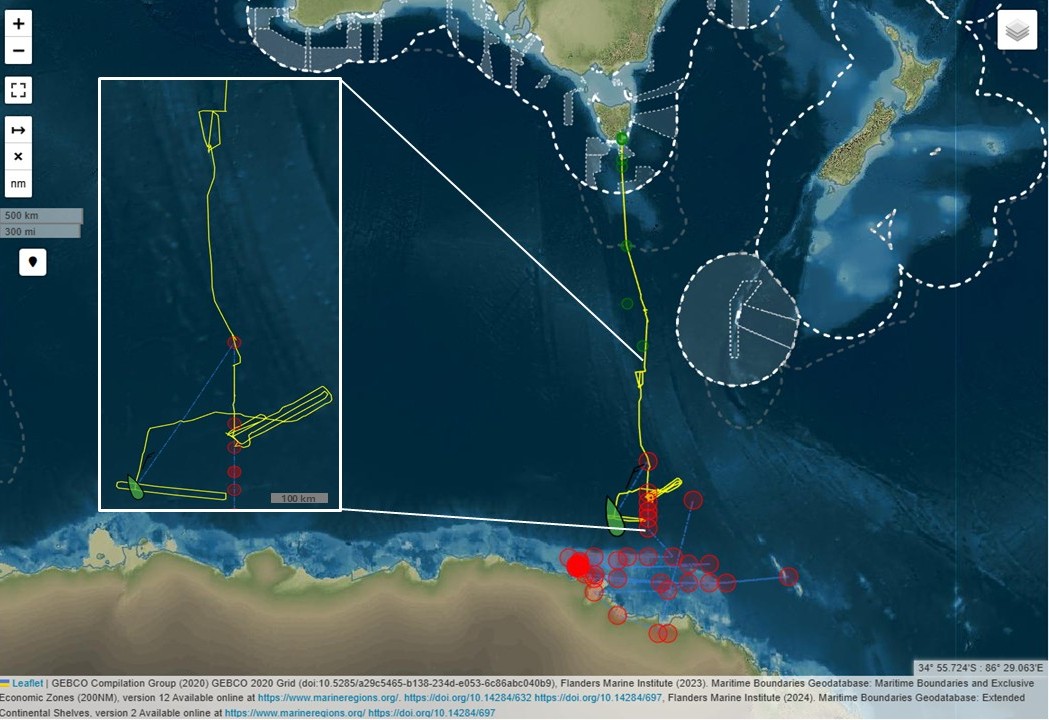

We use sonar and other instruments to map the seafloor and the sub-seafloor (what lies beneath it). These instruments employ sound waves emitted by a source located in a wing-shaped structure called a gondola which is mounted below the bow of CSIRO research vessel (RV) Investigator. The waves transmit through the water, strike the seafloor, are reflected, and return to the vessel. Here, a sensitive sensor records the reflected wave (basically an echo). The sound wave’s travel time tells us the water depth: the longer the travel time, the deeper the water. On RV Investigator, scientists use multibeam sonars that send out many hundreds of simultaneous sonar beams (or sound waves) in a fan-shaped pattern. As the ship navigates across the ocean at a constant speed (~7 knots), the multibeam systems continually collect data about the seafloor, mapping not only directly beneath the ship but also extending out to each side capturing swaths (strips of mapped seafloor) of approximately 10 km wide. In deep water, RV Investigator can map a section of seafloor up to 40 kilometres wide in a single pass. By ‘stitching’ several swaths together it allows us to generate what is referred to as a bathymetric map.

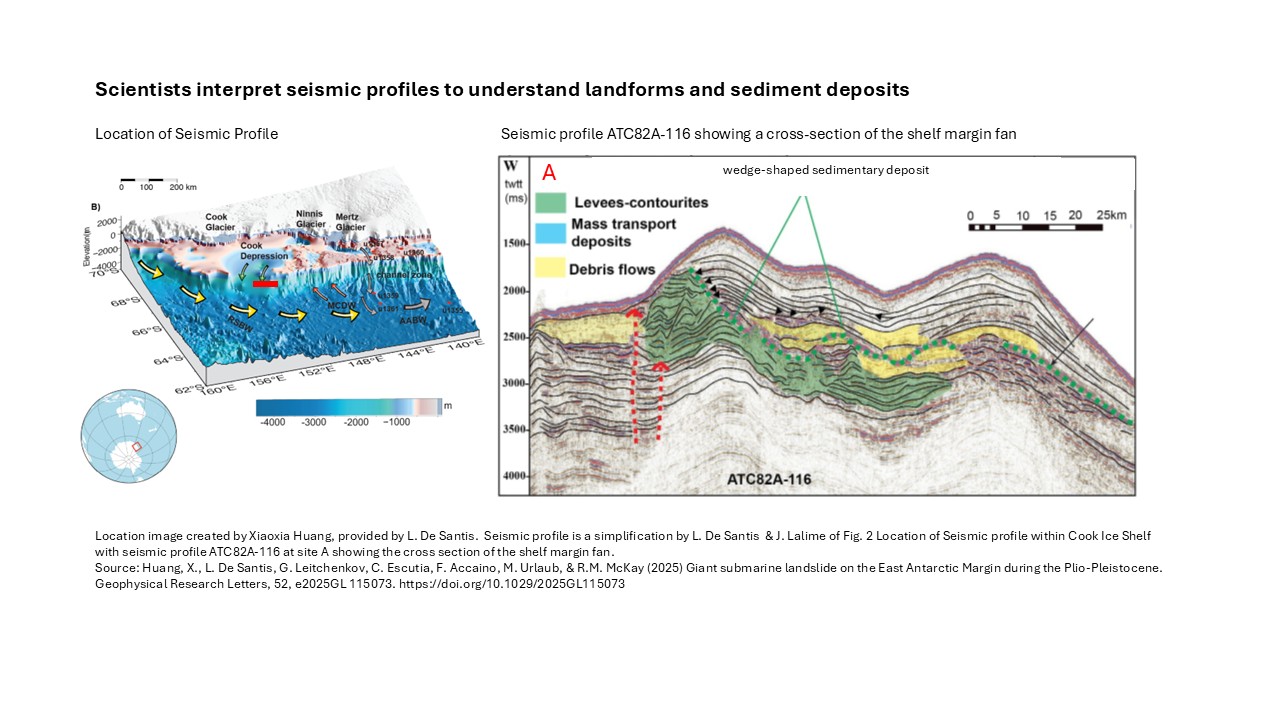

Lower frequency sonar waves can penetrate below the seafloor and are reflected by the surfaces of buried sedimentary layers. Each time the waves encounter a dense surface separating two different sedimentary layers, they are reflected and return to the ship’s sensors. We can then use all the different wave travel times along the ship’s track, reflected by the seafloor and by sub-seafloor layers surfaces, to reconstruct the shape of the sediment layers. We can also work out the sediment’s properties because acoustic waves travel at lower speeds in less dense media. This technique allows the scientist to decide where to sample the sediments to verify sediment type and ensure that sampling equipment doesn’t hit hard rock, as it is designed to penetrate relatively soft sediment.

Despite advances in ocean science, more than 70% of the global seafloor remains unmapped at high resolution. Every new section of detailed bathymetric mapping deepens our understanding of the ocean. On each voyage the RV Investigator contributes to increasing the proportion of global seafloor that has been mapped.

During the Cook Ice Ecosystems and Sediments (COOKIES) voyage the mapping is used by scientists to identify previously unknown seafloor features, and when integrated with other data, better understand marine ecosystems and guide the selection of suitable locations for coring. Mapping in front of current glaciers, reveals hidden ridges and trenches that that influence how warm ocean water reaches and melts ice, helping improve predictions of climate change impacts, including future sea level rise.

Join us on the expedition

The research on the expedition will be showcased through blogs released through the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science and can be followed on social media at Sea2SchoolAU Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and the CSIRO Voyage (IN2026_V01) Page.

This voyage is supported by the Australian Research Council Special Research Initiatives Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (Project Number SR200100008), the Australian Research Council's Discovery Projects funding scheme (DP250100886), the COOKIES GEOTRACES process study GIpr13, Horizon Europe European Research Council (ERC) Frontier Research Synergy Grants, OGS – Istituto Nazionale di Oceanografia e di Geofisica Sperimentale, Securing Antarctica’s Environmental Future (SAEF) (Project Number SR200100005) and by a grant of sea time on RV Investigator from the CSIRO Marine National Facility (MNF).

Top header image: ACEAS/IMAS scientists and CSIRO staff during COOKIES voyage preparations in Hobart (Image Credit: CSIRO/Fraser Johnston)