Southern Ocean may store less carbon than climate models assume

New research led by ACEAS PhD researcher Annika Oetjens and colleagues at the University of Tasmania reveals that the Southern Ocean may be storing less carbon than climate models assume – with important implications for future climate projections.

The Southern Ocean plays an outsized role in regulating Earth’s climate. Circling Antarctica, it absorbs a large fraction of the carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere by human activities, helping to slow the pace of climate change.

But exactly how long that carbon stays locked away in the ocean – and how much ultimately returns to the atmosphere – has remained one of the biggest uncertainties in climate science.

In a new study published in Nature Communications Earth & Environment, the research team takes a fresh look at how carbon sinks through the Southern Ocean, using thousands of observations collected by autonomous ocean robots drifting beneath the waves.

Their findings suggest that one of the most widely used assumptions in climate models may be too simple, and that the ocean could be storing significantly less carbon at depth than previously thought.

Following carbon on its journey into the deep

When plants (phytoplankton) grow in the sunlit surface ocean, they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. When these organisms die – or are eaten by animals like zooplankton – some of that carbon sinks towards the deep ocean in the form of tiny particles.

This process, known as the ‘biological carbon pump’, helps move carbon away from the atmosphere for decades, centuries, or even longer.

“The ocean is a very efficient recycler,” Ms Oetjens explains. “As carbon particles sink, they’re eaten by bacteria and zooplankton, broken up into smaller pieces, or dissolve back into the water.”

Understanding how quickly this happens at different depths is crucial for estimating how much carbon the ocean can realistically store.

A decade of observations beneath Antarctic seas

Directly measuring these processes in the Southern Ocean has traditionally been extremely difficult. The region is remote, stormy and often covered by sea ice.

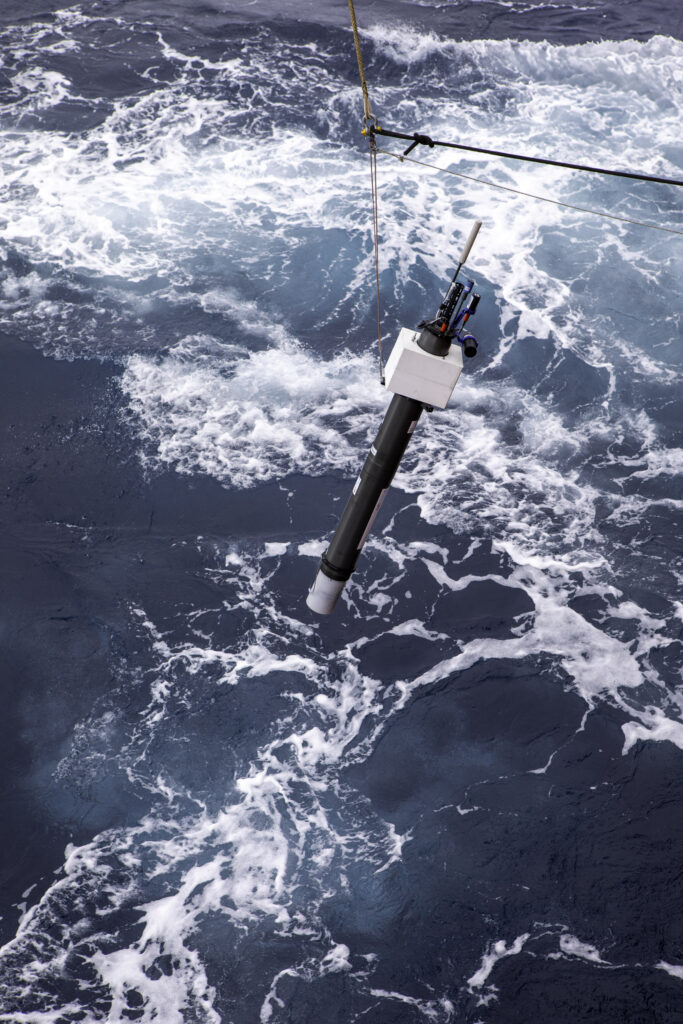

That changed with the rise of biogeochemical Argo floats – robotic instruments that drift through the ocean, diving down to depths of up to 2,000 metres and returning to the surface roughly every ten days to transmit their data via satellite.

“These floats have been a game‑changer,” Ms Oetjens says. “They give us year‑round, depth‑resolved measurements from regions that ships simply can’t access very often.”

Using data from around ten years of Argo float observations, the team tracked how sinking carbon particles weaken with depth – a process known as particle attenuation.

Why a simple rule doesn’t tell the full story

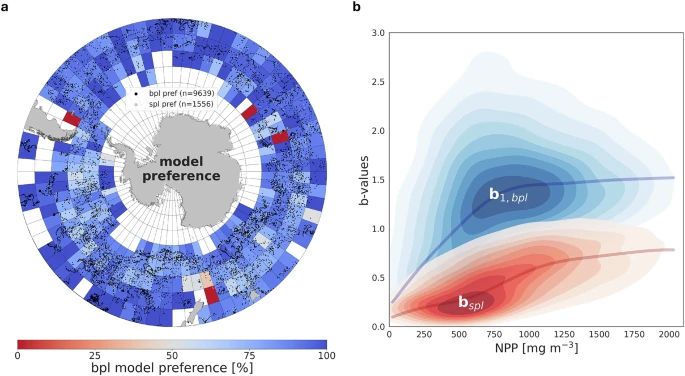

For decades, most ocean and climate models have relied on a rule of thumb to describe how carbon particles break down as they sink: a mathematical relationship known as a ‘simple power law’.

“When we compared this traditional approach to the float data, it just didn’t match what we were observing,” Ms Oetjens says.

Instead of a single, uniform process, the data revealed two distinct layers in the ocean:

- Near the surface: carbon particles are rapidly broken down as bacteria and zooplankton feast on fresh food.

- Deeper down: fewer organisms are present, and some particles – especially those protected by mineral shells – sink faster and survive for longer.

To capture this behaviour, the team developed a ‘broken power law’ model, which treats the surface and deep ocean as two different regimes rather than one uniform system.

Less carbon reaching the deep ocean

The consequences of this shift are significant.

Using the new approach – and matching it to Argo float data – the researchers found that 40 to 60 per cent less carbon reaches certain depths than earlier models predicted.

“In simple terms, the older models assume carbon sinks faster and deeper than it actually does,” Ms Oetjens explains. “That means they likely overestimate how much carbon is stored in the deep ocean.”

Instead, more carbon appears to be recycled in shallower waters, where it can eventually return to the surface, and potentially back into the atmosphere.

What this means for climate predictions

Climate models rely on accurate representations of the ocean to forecast future warming. If carbon storage in the ocean is overestimated, projections of how quickly climate change will unfold could be skewed.

“One important step is making sure our models can reproduce what we’re seeing in the ocean right now,” Ms Oetjens says. “Only then can we be confident about what they might tell us about the future.”

By providing a more realistic description of how carbon behaves beneath the surface, the new findings offer a pathway to reduce uncertainty around ocean–climate feedbacks.

A cautionary note on ocean carbon removal

The results also have implications for proposed ocean‑based carbon dioxide removal strategies, such as iron fertilisation – where nutrients are added to the sea to stimulate plankton growth and increase carbon uptake.

“We did see that more productivity is often linked to faster recycling of carbon,” Ms Oetjens explains. “So even if you grow more plankton at the surface, it doesn’t necessarily mean more carbon is stored long‑term.”

This highlights the complexity of the ocean system – and why interventions may not always have the intended effect.

The need for sustained Southern Ocean observing

Despite the leap forward provided by Argo floats, Ms Oetjens is quick to point out that major gaps remain.

“Ten years of data still isn’t enough to detect long‑term climate trends in a place as variable as the Southern Ocean,” she says. “The better we understand what’s happening in the ocean today, the better prepared we’ll be for what’s coming next.”

Read the paper

Read the full paper: An improved model of particle attenuation reduces estimates of Southern Ocean carbon transfer efficiency by Annika Oetjens, Zanna Chase, Peter Strutton and Tyler Rohr.

Subscribe to our newsletter

For more Antarctic news and stories, subscribe to our mailing list here.