Global circulation and the humble CTD

By Izzy White, University of Southampton (England) and Joline Lalime, Sea2SchoolAU

The world has five ocean basins: Pacific, Atlantic, Arctic, Indian, and Southern with the Atlantic and Pacific basins divided again into Northern and Southern parts.

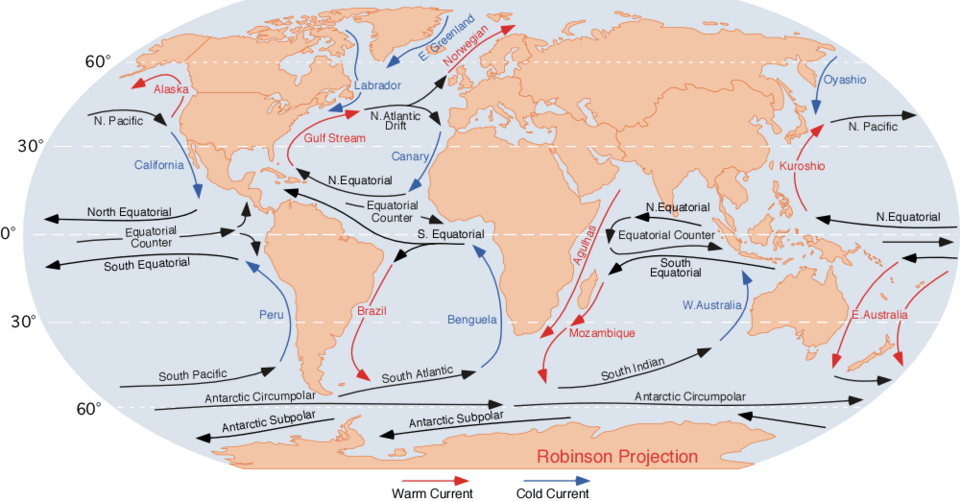

Within each of the ocean basins there is a large scale (thousands of km wide) circular ocean current system, known as recirculation, forced by atmospheric winds. These are called gyres and are important for heat and nutrient transport across ocean basins and therefore support ecosystems which would otherwise have lower nutrient concentration. As well as this, transport of warm waters away from the equator impacts global climate. For example, the UK is at the same latitude as parts of Scandinavia but has a much milder climate due to its proximity to warm North Atlantic gyre. Looking to Alaska, you can start to realise the full effect of the Gulf Stream, keeping the United Kingdom and Eastern Europe warm in comparison.

What is Thermohaline Circulation?

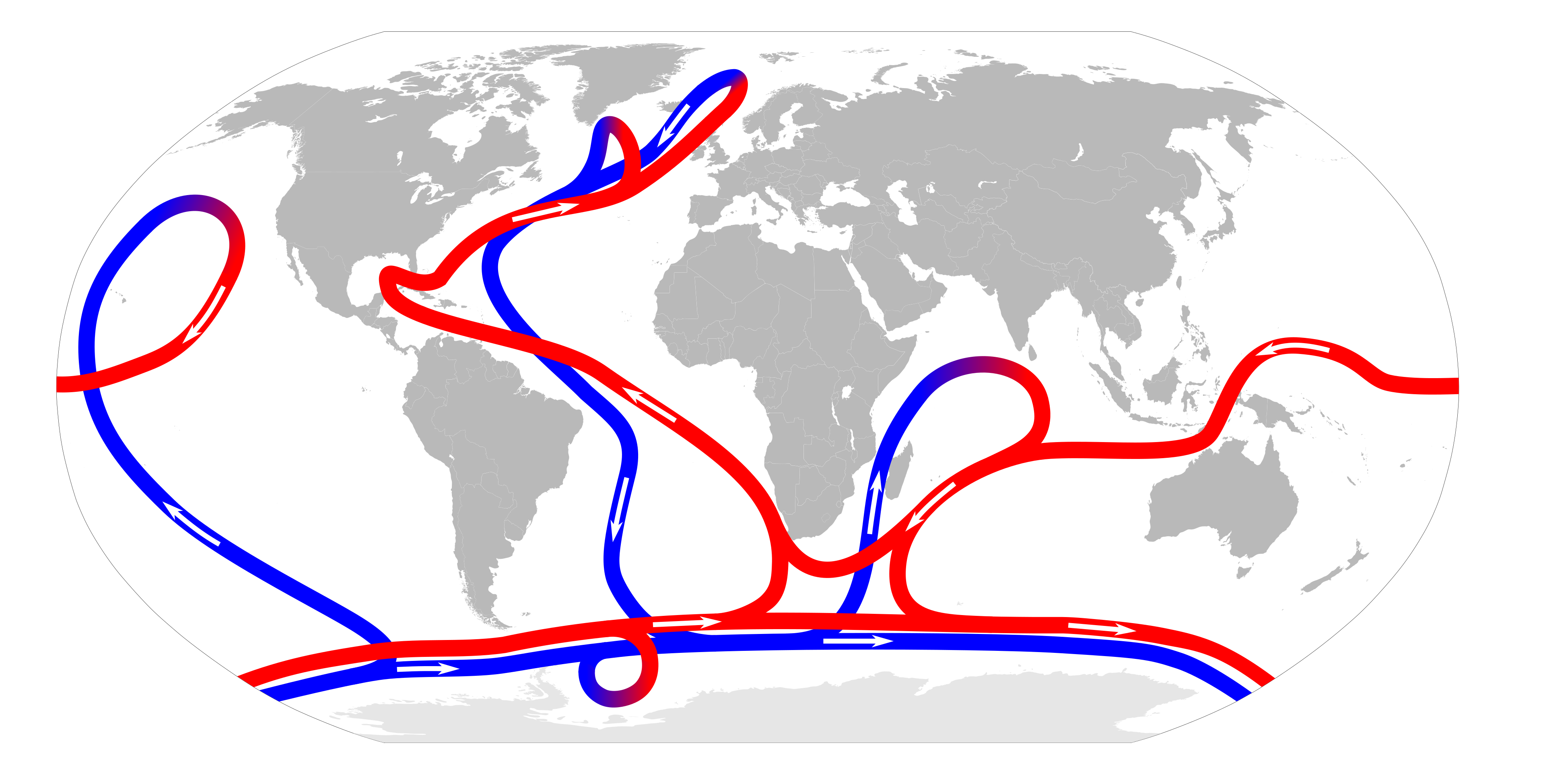

Although gyres have limited impact on vertical (up and down) movement, they transport water with different properties, such as temperature or salinity, which leads to local density differences in the water column. This is a factor which plays a key role in global circulation. The global system of ocean currents connecting the world’s oceans that are driven by changes in density, due to temperature and salinity, is referred to as global thermohaline circulation (THC).

A major part of the THC and perhaps the most well-known example of a large-scale circulation system in the Northern Hemisphere is the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Current (AMOC). If you have heard of it, it was most likely in a conversation surrounding Arctic ice melt and the significant effects and consequences of changes in long-term weather patterns (climate) on natural systems. This includes impacts such as high-latitude (near the poles) cooling and mid-latitude warming. As these waters move northward, cooling and wind-driven surface evaporation occurs which increases density as it becomes cooler and saltier. The higher density water is termed North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) which then sinks to the bottom of the Nordic Seas and is transported south between 1500–4000m below the surface. At the same time, a phenomenon resulting from the Earth’s rotation – the Coriolis Effect - causes the surface water to be deflected to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. This deflection, in conjunction with wind-driven surface waters is called the Ekman effect and impacts vertical movement in the water column. If the Ekman effect leads to water being pushed together (convergence) downwelling occurs and if it is the opposite (divergence) upwelling occurs. This, combined with the strong westerly winds in the Southern Ocean drives NADW upwelling.

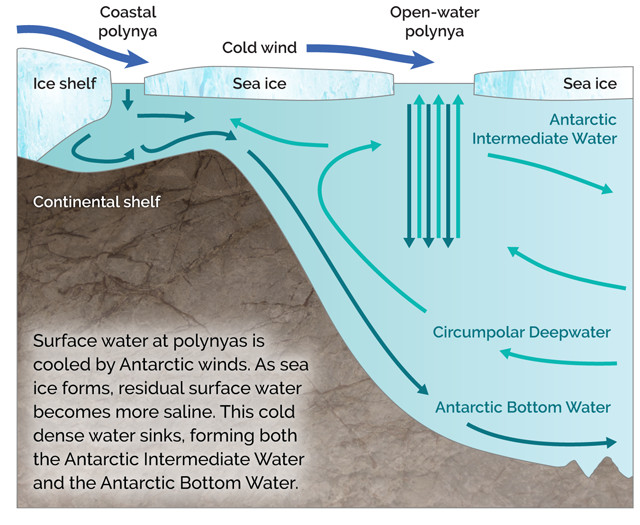

Perhaps less well known is the impact of Antarctica on the MOC due to the formation of Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW). Unlike NADW, this is formed along parts of the Antarctic coastline where gravity-driven, cold, dense air cascades downhill (i.e. katabatic winds), pushing newly formed sea ice off the coast, increasing the local sea ice production. The result is a surface ‘salty brine’ which is extremely dense and thus sinks to the shelf, either forming Antarctic Intermediate Water (AIS) or AABW depending on whether it is supercooled by the iceshelf before flowing down the slope. The high salinity and low temperature of AABW mean it is even denser than NADW and so dominates the abyssal part (3000–6000m) of the ocean and accounts for approximately one third of the ocean’s total volume.

Although these water masses, as well as Antarctic Surface Water (ASW), have distinct temperatures and salinities the Southern Ocean is home to the world’s largest ocean current: the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC). The ACC drives mixing in varying proportions and forms a warmer (>3.5°C above local freezing point) salty layer called Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW). This layer is critical to understanding regional melt rates in Antarctic because it can cause rapid basal melt – melting of ice shelves from underneath and increase their instability.

With its layers, upwelling, downwelling, bottom water, intermediate and surface water – it is clear the ocean is not a simple two-dimensional system. This complexity is part of what makes studying the Southern Ocean so challenging. That and the sea ice. Since the launch of the first near-global satellites in 1972 (the Nimbus5 and Landsat1/ERS) our understanding of the Southern Ocean has accelerated, and we can observe the surface properties of the ocean like sea surface height and temperature to calculate gyre size and strength as well as fluctuations in the ACC location remotely. There is even research inferring water column properties from surface changes. However, satellites cannot ‘see’ into the ocean.

Queue the CTD

A CTD is a Conductivity Temperature Depth instrument which measures a range of water properties as it is lowered to the ocean floor. This data is reported live to the Operations Room on CSIRO research vessel (RV) Investigator so we can choose the depths at which to use the bottles on the CTD carousel (frame) to collect water for biogeochemists, molecular biologists, and DNA researchers to analyse later. As this research is so hard to conduct, other instrumentation is often mounted to the CTD to improve the breadth of data collected per cast (the term for one deployment). On RV Investigator, this includes a lowered acoustic doppler current profiler (LADCP) and a mounted camera.

In physical oceanography we use temperature, salinity and current data (from the LADCP) and draw on other attributes like the chlorophyll level, to untangle our findings. As each water mass has a particular ‘fingerprint’ we can identify the presence of fresh melt water or warm CDW as we approach the slope. Combining this with satellite data relating to an ice sheet’s velocity, we can start to investigate: are specific ice shelves subject to basal melting?

With this question mark hanging over the Cook Ice Shelf the COOKIES voyage scientists are hoping to explore summer on-shelf conditions which will help understand potential impacts of climate change in the future.

Join us on the expedition

The research on the expedition will be showcased through blogs released through the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science and can be followed on social media at Sea2SchoolAU Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and the CSIRO Voyage (IN2026_V01) Page.

This voyage is supported by the Australian Research Council Special Research Initiatives Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (Project Number SR200100008), the Australian Research Council's Discovery Projects funding scheme (DP250100886), the COOKIES GEOTRACES process study GIpr13, Horizon Europe European Research Council (ERC) Frontier Research Synergy Grants, OGS – Istituto Nazionale di Oceanografia e di Geofisica Sperimentale, Securing Antarctica’s Environmental Future (SAEF) (Project Number SR200100005) and by a grant of sea time on RV Investigator from the CSIRO Marine National Facility (MNF).

Top header image: ACEAS/IMAS scientists and CSIRO staff during COOKIES voyage preparations in Hobart (Image Credit: CSIRO/Fraser Johnston)