New model correction improves predictions of Antarctic ice shelf melt

Accurately predicting how Antarctic ice shelves melt is critical for understanding future sea-level rise and global climate change. A recent study led by ACEAS PhD researcher Claire Yung from the Australian National University introduces a correction to ocean models that could significantly improve these predictions.

Published in The Cryosphere, Ms Yung’s research tackles a longstanding challenge: how to represent the complex turbulence beneath Antarctic ice shelves in large-scale models. These ice shelves act as buttresses for the Antarctic Ice Sheet, and their stability determines how much ice flows into the ocean. If they melt faster than expected, global sea levels could rise dramatically.

“Antarctic ice shelf melt has implications for the whole planet, not just Antarctica,” Ms Yung explained. “If the ice sheet loses mass, it goes into the ocean and raises sea levels everywhere, including around Australia.”

The challenge

Ice shelves are melting from below as relatively warm ocean water circulates in cavities beneath them. This process is driven by turbulence – small-scale motion that global models currently don’t resolve. Instead, models use simplified equations called parameterisations to approximate these effects.

“Models can’t resolve all the small-scale processes that actually drive melt,” Ms Yung said. “Their grid boxes are too big to account for turbulence and other dynamics, so we use parameterisations to describe the net effect of that small stuff.”

But these approximations come with uncertainty. Without enough observational data from Antarctica, it’s hard to know if models are getting it right. That uncertainty feeds into predictions of ice shelf melt – and ultimately, sea-level rise.

Current parameterisations often assume certain factors don’t change whereas real-world conditions can vary. For example, they may ignore how different layers of the ocean act to suppress turbulence, reducing heat transfer to the ice. When models overlook this, they could dramatically misestimate melt rates.

“We’re dealing with huge levels of uncertainty,” Ms Yung said.

Why improving predictive capability is crucial

Accurate melt predictions are essential for planning coastal infrastructure and adaptation. Current projections for sea-level rise in Australia range from about 60 centimetres to 1.1 metres by 2100 – a gap that carries enormous implications for where communities can live, how governments allocate resources, and the scale of future adaptation measures. Approximately 85% of Australia's population live in coastal areas, exposed to risks from sea-level rise.

“We’re working to make more accurate ice shelf melt and sea-level rise predictions because that helps with being prepared for the future,” Ms Yung said. “It’s about making informed choices and adapting in time.”

Beyond sea-level rise, changes in melt influence global ocean circulation. Increased freshwater from melting ice shelves can slow the overturning circulation, affecting climate systems worldwide.

How the new correction works

The researchers developed a new way to improve ocean models by better accounting for how meltwater affects the movement of heat beneath ice shelves. They used the results of detailed simulations that show that meltwater can form layers that calm the water and reduce mixing. Instead of treating this effect as fixed, the new approach allows it to change depending on how warm the water is and how fast it is moving. This approach captures the fact that different ice shelf cavities behave differently – for example, warmer cavities are more affected by layering that reduces mixing than colder ones.

Improved predictions of melt

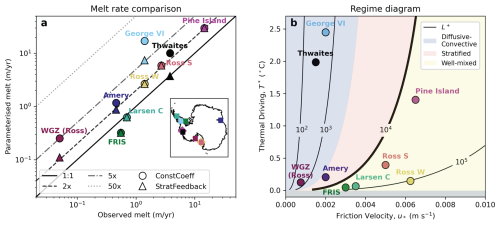

When tested against observations, the new approach improves melt predictions compared with the most used current scheme. Incorporating the new approach into ocean models also revealed how strongly the system responds to these choices.

“The most surprising thing was how sensitive the whole system is,” Ms Yung said. “If you add a bit more melt you accelerate circulation in the cavity, which increases ice melt even further. There are all these self-reinforcing feedbacks.”

Understanding stratification

Beneath many Antarctic ice shelves, the ocean is divided into layers – called stratification – because the water has different temperatures and saltiness. These layers reduce mixing in the water, which means less of the warm water can rise up to melt the ice. The study found that when parameterisations don’t account for this layering, they often predict too much melting – especially in warmer conditions with little mixing, like those beneath parts of the Pine Island Glacier.

“This layering – or stratification – changes how heat moves,” Ms Yung explained. “If turbulence is suppressed, less heat reaches the ice, so melt can be much lower than equations in the models predict.”

These conditions are believed to be relatively common beneath Antarctic ice shelves, especially in West Antarctica. Capturing this dynamic is essential for improving melt predictions and reducing uncertainty in sea-level rise projections.

The findings suggest that some ice shelves could be more resilient to ocean warming than previously thought, but others could also be more vulnerable.

What’s next

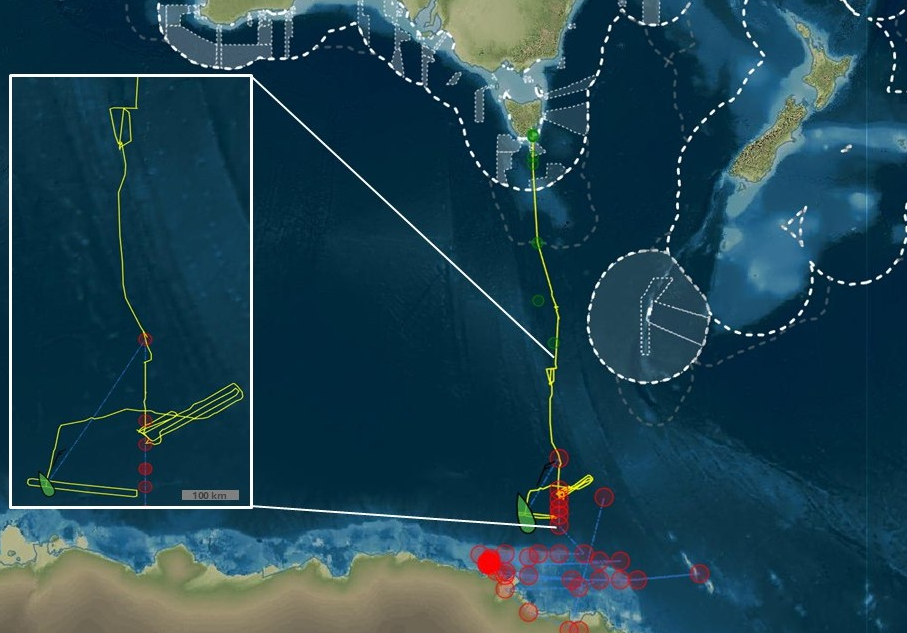

Ms Yung says the next step is to test the new scheme in full-scale Antarctic simulations using ACCESS-OM3, the ocean component of Australia’s new climate model, which now includes ice shelf cavities for the first time. Collaboration with observational teams is also crucial.

“The biggest challenge is the lack of data,” Ms Yung said. “We need more in-situ data collected from fieldwork in Antarctica where we can measure melt and ocean conditions in the same place. Every improvement in our understanding brings us closer to predicting the future of our coastlines – and helping the communities that depend on them.”

Read the paper

Read the full paper: Stratified suppression of turbulence in an ice shelf basal melt parameterisation by Claire K. Yung, Madelaine G. Rosevear, Adele K. Morrison, Andrew McC. Hogg, and Yoshihiro Nakayama.

Subscribe to our newsletter

For more Antarctic news and stories, subscribe to our mailing list here.