Interview transcript – Australia’s Antarctic science funding: the crisis is now

“The crisis is this year, it’s right now. That’s the conversation we’re trying to get across with our elected officials.” – ACEAS Director, Professor Matt King speaking with ABC Hobart’s David Reilly.

*The following is a transcript of a radio interview on ABC Hobart’s Drive program, on 17 June 2025.

—

Professor Matt King: The Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science was originally funded for three years from the Australian Government. It’s a large grant by almost any measure, in Australian science. There’s $20 million over that three-year period.

With COVID, and delays to Australia’s amazing new icebreaker Nuyina means that we’ve spent that more slowly and we’re running out over four and a half years. It means we wind up in the middle of next year and that’s a cliff, because there’s no mechanism for us to reapply.

We are doing the necessary work now of talking to Government, talking to politicians. And of course that’s an entirely reasonable thing to have to do if you’re funded with substantial amounts of money – you want to be able to talk to your funders about what you’ve done with it – and show the value of that work, whether that’s the research or the training and development of early career researchers.

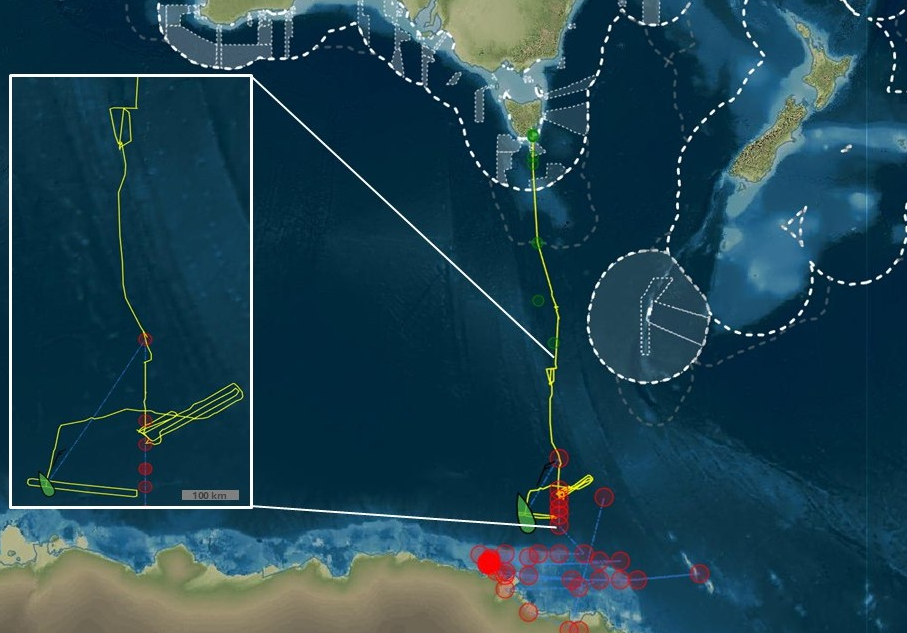

But Antarctic research in particular doesn’t work well over three year, four year funding cycles. We proposed the work that we’re doing in 2019. Part of the work that we’re doing included the maiden voyage of the icebreaker Nuyina to the Denman Glacier in East Antarctica, that just happened this year six years later.

And now we’ve got buckets full of data and samples that need to be turned into information that’s useful for policymakers and the broader scientific community. And that can’t be done in a 12-month period.

Presenter David Reilly: You’ve just got back, some of your researchers. How many researchers were on the latest voyage?

Prof. King: There were 60 scientists in total and our program and our Centre supported 33 of them.

Presenter: The first science voyage of the icebreaker and half of the science teams on board were your own. I’ve seen some photos, all sorts of samples and rocks and measurements and no doubt just terabytes of data of everything. But, uncertainty at the moment about whether you’ll ever have the resources to crunch those numbers?

Prof. King: Yeh, that’s right. We’re hurrying up and getting as much done as we can in the next 12 months, but our researchers are also looking and thinking about their own careers. And a lot of the people on board were early career researchers who were just starting off.

They’re thinking, well where is my next pay packet coming from?

And they’re so good and in such demand that they will jump to opportunities in Europe, in Japan and New Zealand – and they’ll jump early. They’re not going to wait until the end of their contract to do that, they’ll take the next opportunity.

So while a year away might seem a long way away in some schemes, in a competitive and international scientific environment the crisis is right now. We’ve seen people leave and have seen people leave for secure employment or opportunities overseas already. So we feel the crisis is emerging now, and of course every person who leaves early, that’s another little bit of work that hasn’t been completed and that we’re not going to be able to do in the timeframe that we have available.

Presenter: How do we compare to our competitors, at least when it comes to scientific talent? There’s a limited pool of really skilled and talented scientists – how do we compare when it comes to being able to offer long term job security?

Prof. King: There’s a variety of contract lengths, there’s sort of three years at the lower end and there might be research positions at the other end, where they’re dedicated to doing research over many years and longer periods of time.

The global environment is quite tricky right now because the US is very much in a declining phase and other nations are looking to step up into the gap. There has been some very strong attempts to recruit some of the best people into Europe on the back of that, and so we’re seeing potentially a rebalancing of that.

But regardless of how it works around the world, we know that Antarctic science works best on 10-year time scales.

It really does take that long to plan a voyage, execute a voyage or a piece of fieldwork on land, to take it up to something that would help improve our prediction of the future of Antarctica for instance.

Presenter: Are you a bit over it Matt, the hand to mouth existence of every few years having to go back to find the bucket of money, to pitch in for it, when this is time that could be spent planning science, rather than planning funding pitches?

Prof. King: If I put my taxpayer hat on, I think we run a very inefficient system when we try and stop things and start them again. We’ve had that in Hobart in recent years, where there was a large centre that was spun up in 2014, it ran until 2018, it stopped and my centre bid. We started in 2021. All the effort associated with finishing and starting again, that’s missed opportunity, missed momentum in terms of building Australia’s capability.

I don’t want to give the impression that this is scientist-focused. Of course the scientists are super important to me and they’re important and critical.

But this is really about getting information that’s valuable to people who are concerned about Australia’s coastlines, the Pacific, sea level rise, changes to our marine ecosystems, to fisheries, impacts of melting sea ice in Antarctica that we’ve seen so dramatically in recent years on Australia’s weather and climate.

These are important things for the nation and I see that we’re not organising ourselves in the most efficient and effective way.

Presenter: I wonder if the way that we’ve organised it has also set up some perverse incentives, Matt? I mean essentially what you’re doing is you’re pitching to politicians for funding. Politicians love an announceable, something that’s easy to sell in a press release and looks great. But the truth is a lot of the work that’s done in science, most of the really important work is difficult to distil in a big ribbon-cutting event. Are we seeing funding just flowing to the wrong places because some of it looks better, it’s flashier?

Prof. King: I don’t think that’s the case. When I talk to politicians, especially here in Tasmania there’s no doubt that there’s a commitment to substantial Antarctic activity in Tasmania. They understand the importance to our economy, the Antarctic sector, whether that’s the industries that support the work – the engineering firms and the construction firms, all those sorts of things, the groups that resupply the ship.

But all of that happens because we have science here in Hobart. If there wasn’t a substantial science presence, then all of that would start to diminish away. So I think the politicians get it and get the importance of it. It is challenging when you have so many other things in your diary, you’re waiting for a crisis to arrive.

Part of the discussion that we’re trying to have now is that the crisis is not in May and June next year when the money is about to run out, because the cupboard will be bare at that stage in terms of our researchers.

The crisis is this year, it’s right now. That’s the conversation we’re trying to get across with our elected officials.

—

Presenter: Matt King, we really appreciate you coming in and we’ll keep tabs on how you’re going with the renewal of funding for ACEAS.

Prof. King: Thanks for making time David.

Presenter: Professor Matt King there, with ACEAS – the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science – they have about a year left of funding, but now is the time to be planning 12 months ahead and as that funding cliff approaches, they are looking for a fresh source of funds.